Postcards as artifacts, ephemera, and personal documents

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Emily Drachman and Julia Lee, Collections and Curatorial Summer Interns

August 5, 2021

Have you ever sent or received a postcard? If you haven’t sent one yourself, you’ve likely seen a rack of postcards for sale at a souvenir shop at some point.

Unlike many artifact types in the Seaport Museum collections and archives, postcards are still being printed, purchased and sent around the world, including at Bowne & Co., the Museum’s historic letterpress print shop. Compared to scrimshaw, clipper cards, and mucilage bottles, postcards are something that most people are familiar with and need little explanation.

But, as the old saying goes, does familiarity breed contempt? Are postcards valuable enough to be part of a museum collection? Of course they are!

In this blog we’re going to explore the origins of the format of postcards, their uniqueness as historical documents and voices of the past, and the importance of correctly cataloging these precious pieces of ephemera we were lucky enough to research and catalog over the past few months.

Brief History of the Postcard

The late 1800s were some of the most innovative times in American history in terms of communication. The United States Postal Service was established in 1775, just before the US would sever their ties with Britain, with Benjamin Franklin as its first postmaster general. Thanks to this new government-supervised system, more people were now able to communicate with the rest of the world, with virtually all civilians being able to send and receive mail for relatively cheap. By the turn of the 20th century, the US post office was beginning to resemble what it is today with the introduction of stamps and registered mail. Communication was now fast, safe, and, most importantly, accessible.

So, you can now send anyone anything from all over the world. Where do you even start? Even though photos had just been invented, they were still pretty expensive to get a hold of. Printing companies started to catch on that this could be a great opportunity to increase circulation of this new invention, while also keeping it cheap enough for the public to enjoy.

While mail circulation in the US was largely controlled by the US Postal Service, the first postal card in the United States was actually copyrighted by John P. Charlton in 1861, just after Congress passed a bill allowing privately printed cards to be sent in the mail earlier that year. It wasn’t until the early 1870’s that the government would receive that same privilege. On May 1st, 1873, the first government-produced postal card was issued. When postal cards started to get more popular, the government required all privately printed postcards to be sent with a 2-cent stamp, rather than the typical 1-cent stamp required for government printed cards (the price of postcards was reverted back to 1-cent in 1898).

The postal card was an instant success! The New York Times reported that clerks all over the city sold over 200,000 postcards in two and a half hours. Between May and September of 1873, over 64 million postcards were bought nationwide.

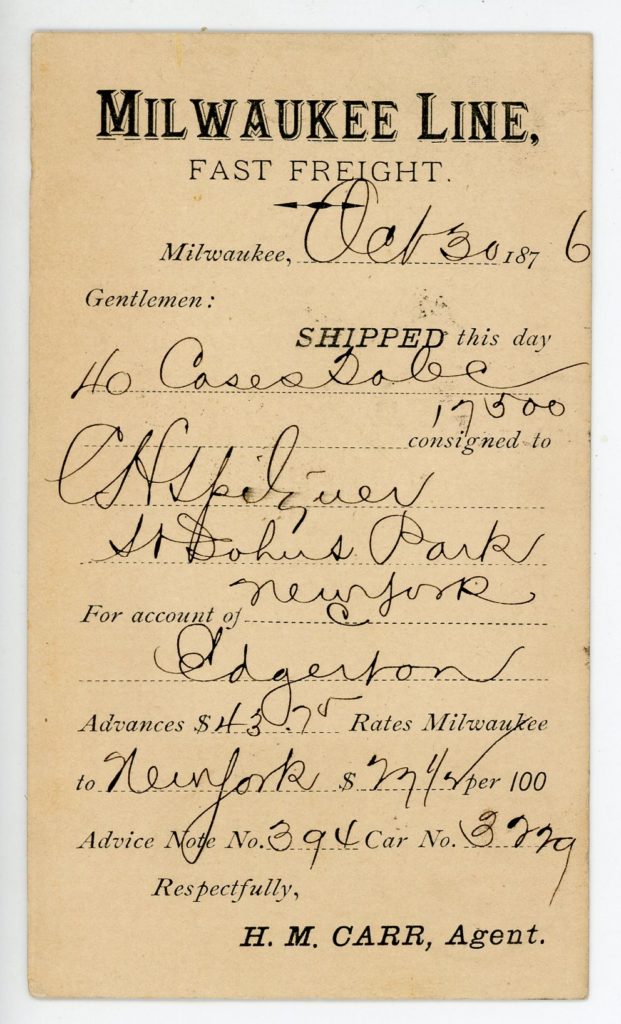

Some of the earliest postal cards look very different from how they are today. Here is an image of the earliest postcard in the Museum’s collection.

You’re probably wondering how this is even considered a postcard…it doesn’t even have a photo! Photos on postcards (or postal cards) also didn’t become popular until 1902 when Kodak began making paper and cameras that accommodated the postcard’s size.

In 1876, government-distributed cards were only a few years old. They went by the name “postal cards.” They were used for lots of things and had a variety of messages! Some were sent for business purposes (like this postal card at left), but others talked about all sorts of things! In 1903, the Baltimore Sun, commented that people were getting too comfortable with what they wrote on these postal cards, citing a woman who wrote about a fight she had with her husband.

[Milwaukee Line Fast Freight Shipment Postal Card Note], October 30, 1876. South Street Seaport Museum 1980.252

At this time, only government postal cards were allowed to use this name. Therefore they called postal cards from private companies “postcards.” Postal cards and postcards were at fierce competition with each other during the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Now, in general, we use the term “postcard” and “postal card” interchangeably, since the difference is incredibly slim. From now on, I will refer to both types as simply “postcards.”

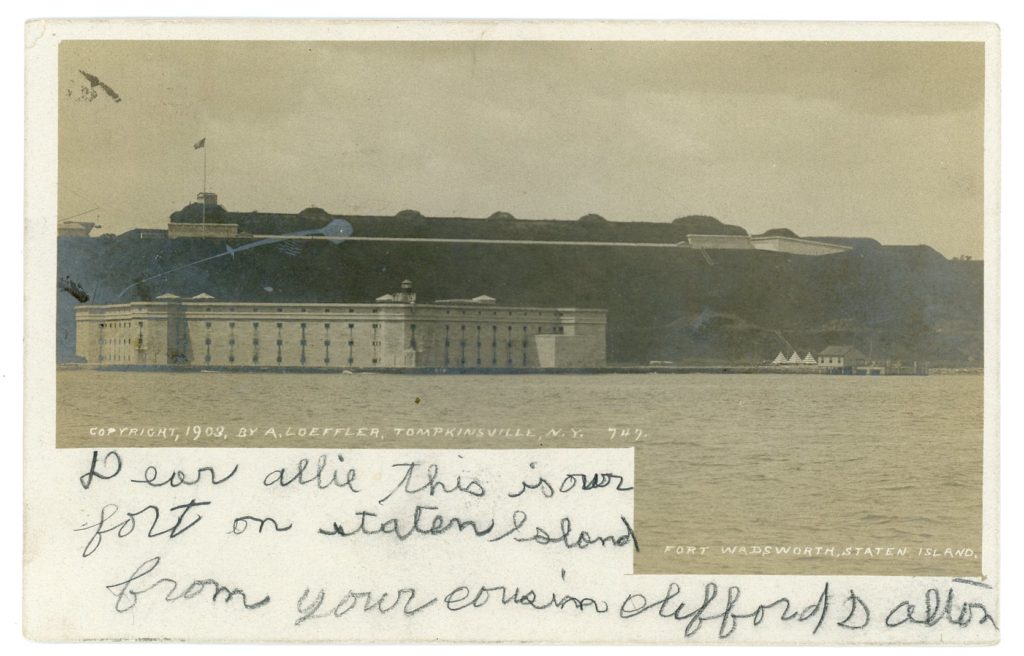

The postcard’s popularity hit its peak between 1907 and 1915 in what was called the “Golden Age” of the postcard. A few new policies in postcard production were able to make this possible! The most notable change to the postcard’s design was the divided back. Before 1907, the back of the postcard was reserved for the address only; all messages were required to be written on the front along with the image. Messages could only be about a few words, or a full sentence if you could write small enough.

“Fort Wadsworth, Staten Island” January 10, 1907 (postmark date); 1903 (photograph). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0447

Prior to World War I, postcards from the United States were mainly printed in Germany. However, things started to change starting in 1915 when political tensions arose, and we had to start printing locally. In order to preserve material and cut costs for the war, postcards were printed with smaller images and on flimsier paper. People were disappointed with this change, thus ending the “Golden Age of Postcards.” Nowadays, we use what are called “photochrom-style” postcards, which have a glossy finish and resemble real photographs. In the age of the internet, postcards are more typically collected as souvenirs rather than tools of communication. However, USPS reported that in 2013 nearly 3.5 billion postcards were mailed.

Postcard as Historical Documents

To the Museum, postcards are very important pieces of information that allow us to look back in history (and don’t worry, we have plenty of them.) Over the course of my internship, I researched and cataloged almost 40 postcards ranging from the early 1900’s to the sixties… and that doesn’t even scratch the surface of our collection. I want to show you some of my favorites I got to work on, and how each one helped me learn more about another.

“New York Skyline and East River, New York” ca. 1916 (photograph). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0175

This postcard dates to around 1916, but it took a bit to get to such an exact date that I can be fairly confident about. Ultimately, I found this exact image in a New York Times article with the same photographer credits, but what helped me most to identify this image was by looking at the skyline. I don’t know much about battleships, but I’ve lived in Lower Manhattan for years, so I know my early 20th century skyscrapers. The Woolworth Tower, completed in 1912, was the tallest building in Lower Manhattan until the construction of the Manhattan Company Building in 1929, and in this image, the Manhattan Company Building is nowhere to be seen. Therefore, this image could be dated roughly between 1912-1929. There are several ways I could have gotten to this estimate, but this is how I did it first. Now that I knew what this image was about, it was time to learn from it.

As I learned through a little more digging, I identified this ship as the USS Wyoming. This postcard, instead of a mysterious glimpse into the past, was now a historical document! I now knew that USS Wyoming had visited Brooklyn Navy Yard shortly before entering WWI. Since postcards are incredibly widely circulated, it also helped me understand what kinds of images the public liked to see and send on postcards.

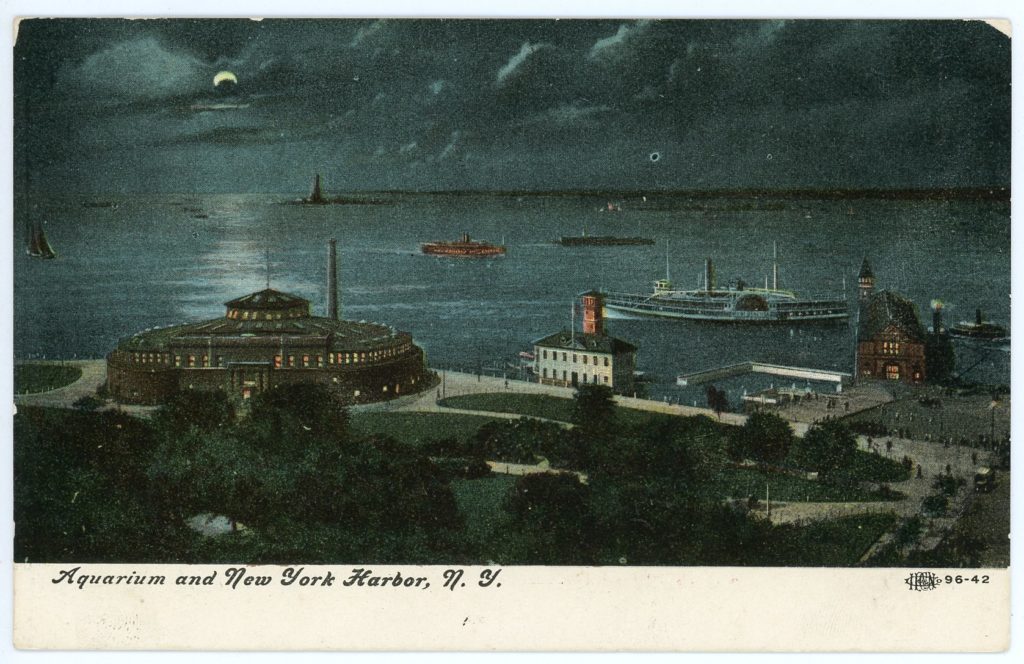

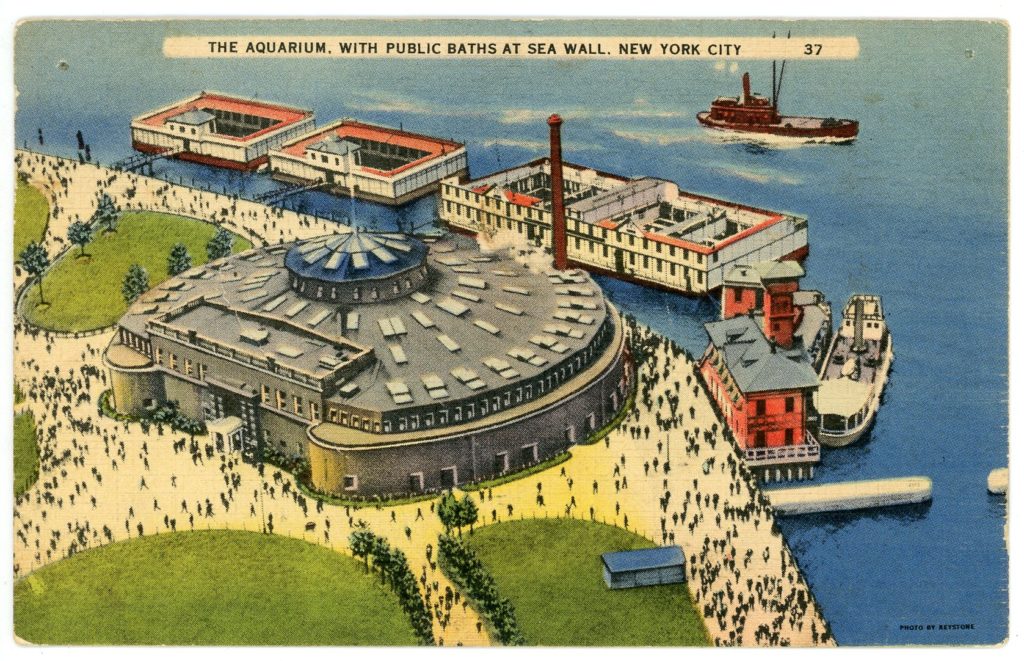

Left: “Aquarium and New York Harbor, NY” 1907-1915. Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0019

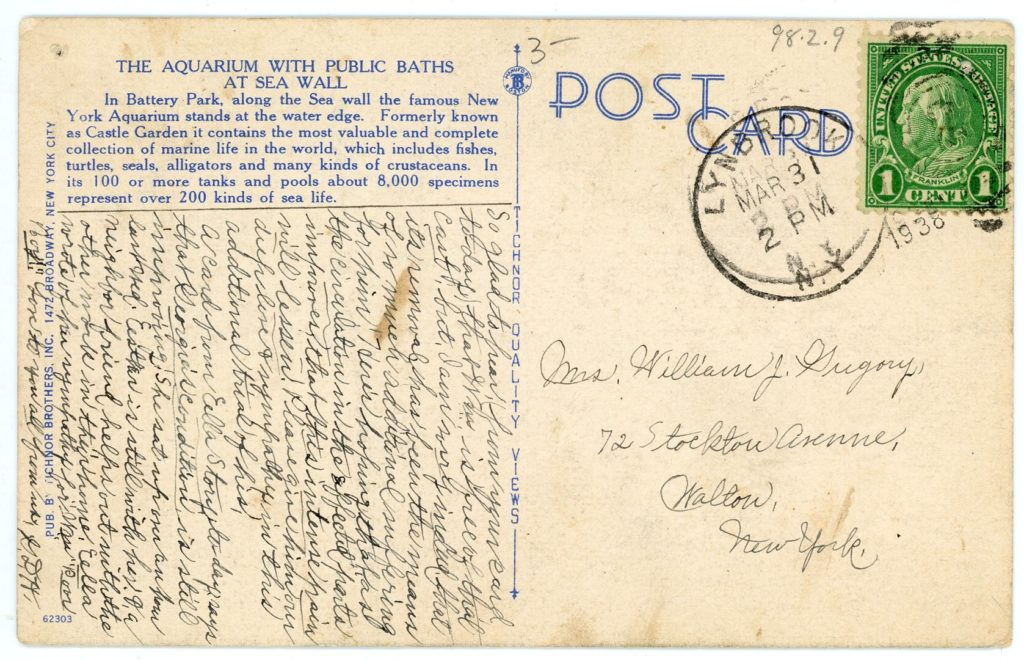

Right: “The Aquarium and the Public Baths at Sea Wall, New York City” March 31, 1938 (postmark date). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0009

Here’s a subject I saw a lot of while cataloging this particular collection of postcards! Castle Clinton has a whole lot of history. Starting out as a fort, this building has been through a rollercoaster of different attractions. It was an entertainment center, an aquarium, an immigration center, etc. In this image, Castle Clinton is called the “New York City Aquarium,” which remained in use from 1896 to 1941. It makes sense why this would be such an interesting subject for a postcard, its dates of operation even fall right in the postcard’s most popular years!

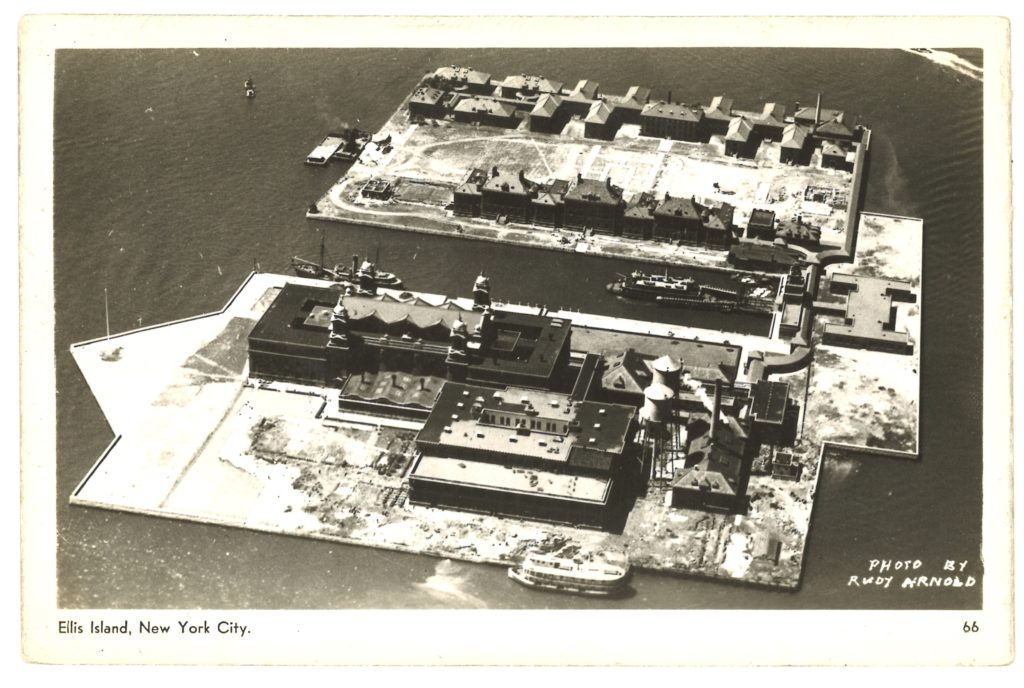

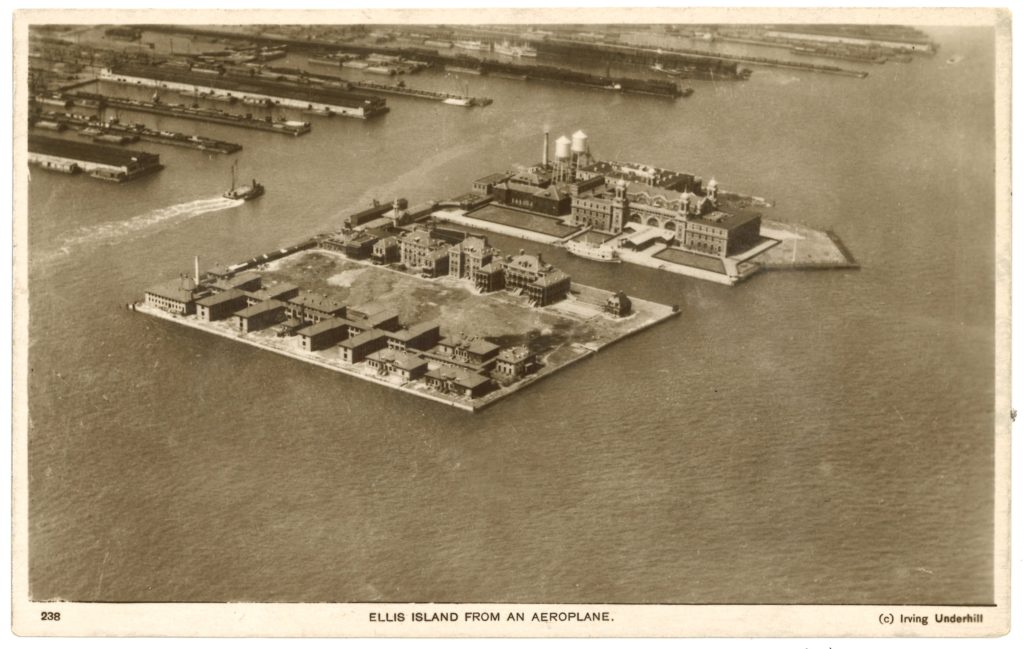

Left: “Ellis Island, New York City” 1892-ca.1900 (photograph). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0301

Right: “Ellis Island from an Aeroplane” n.d. Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0302

These postcards give us a snapshot of history along with a little image, they really feel like a frozen piece of time you can touch (with gloved hands, of course.) Here are a few images of Ellis Island’s main building taken just a few years apart. These postcards actually track the completion of the transformation of the building into what it is today. The main building has had a few looks over the course of Ellis Island’s years as the immigration center as can clearly be seen above. The first postcard even claims to be taken from an airplane! These are just a few examples of how postcards can act as documentation of history!

Postcards as Voices of the Past

While every object in the Museum’s collection has something to tell us about New York City and its history as a world port, few can speak to us as directly as a postcard. In their function is the spreading of information, and from them we are able to glean personality, events, and moments from people’s lives no matter how small or mundane. Postcards that were sent all contain a message someone thought was important enough to write down and send to someone, but beyond the words they write, we can see how they wrote it. Is their handwriting messy or neat? Were they rushing to write their message? Do they use fancy calligraphy? How do they sign, with just their name, or with love from? Postcards allow us to look at more of the everyday communications and connections between people.

While not all of the Museum’s postcards went through the mail and include handwritten messages, many of them do. It’s through these messages that we are able to hear the voices of the past and I’d like to share a selection of some of my favorites which will begin to show you some of the variety in the collection.

“Dear May.

I want to

thank you for what you sent to my cat you don’t

know how much she

injoyed [sic] it. We are hav

ing summer weather now

How are you injoying [sic] it

Good bye [sic] | From Florence

Haines”

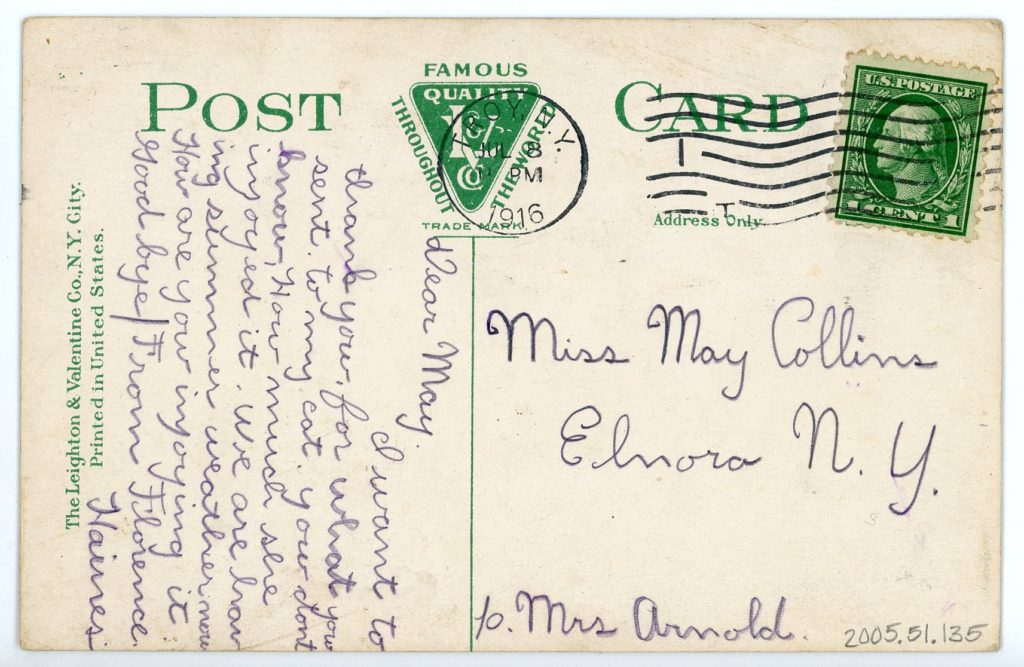

“SS “Rensselaer,” Hudson River, N. Y.” July 8, 1916 (postmark date). Gift of Wendell Lorang, 2005.051.0135

This postcard contains a sweet message from Florence, thanking Miss May for what she sent to Florence’s cat. Florence’s handwriting is neat in the way that someone who is just learning cursive writes very carefully after much practice in a workbook. This along with her misspelling of enjoy with an i, as the word sounds, could lead us to believe that Florence is quite young. So while postcards may not usually have a lot of concrete information on them, there is a lot to be learned from them about the people who wrote them.

Short and sweet messages like this are common on postcards, but sometimes people have more to say and are able to write small enough to put a longer message such as this postcard from G. D. H.

“The Aquarium and the Public Baths at Sea Wall, New York City” March 31, 1938 (postmark date). Gift of Norman Brouwer, 1998.002.0009

This longer message of sympathy is fit on the back of the postcard in small tight handwriting, and it reads more like a letter in some ways. It is likely that G. D. H. fit this message on the back of a postcard in order to avoid paying to send a letter which would have cost 3 cents in 1938 when this postcard was sent rather than the 1 cent stamp which is on the postcard.

Due to their price, postcards in the early 20th century were the best way to update someone on your travels, or just send a quick message. Many postcards include messages to let someone know the sender has arrived at their travel destination, or back home from a trip, or any other quick notes. Between the inexpensive cost and the limited space for a message, postcards often took on a casual tone like this postcard including a short update message from Frank to his siblings,

“2-27-1908

Dear Sister and Bro. Just in on business for

today. Will write you a letter if I get time later.

Frank.”

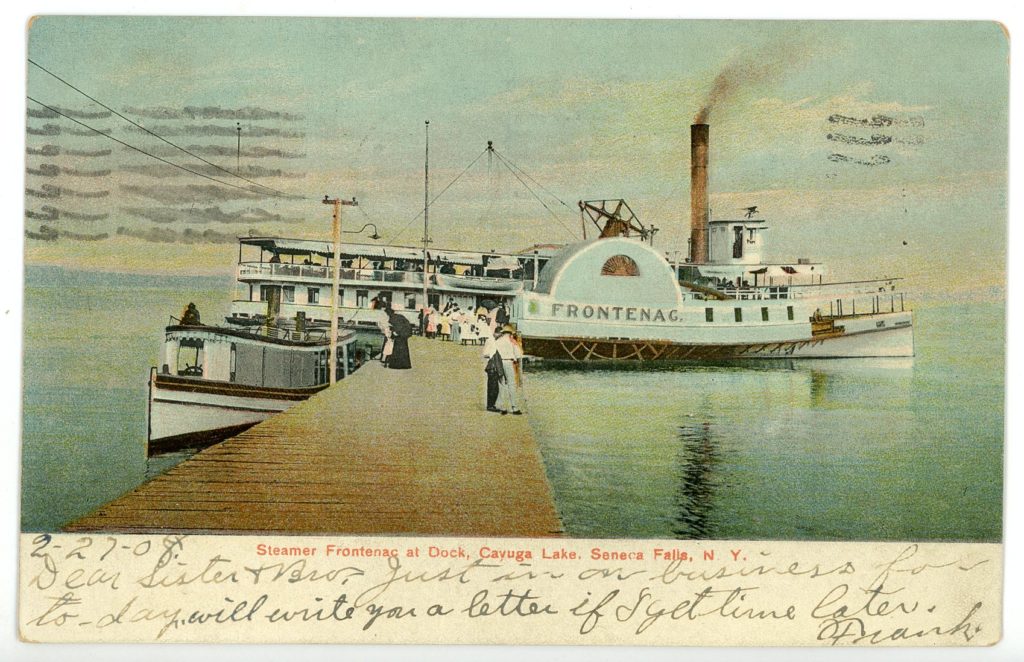

“Steamer Frontenac at Dock, Cayuga Lake, Seneca Falls, N.Y.” February 27, 1908 (postmark date). Gift of Wendell Lorang, 2005.051.0149

Frank’s message gives an insight into attitudes about postcards and letters. Especially being a message on the front of the card, there is only room for the most important information for his sister and brother—he has arrived. If Frank has the time, a letter is perhaps a better way to go into more depth and perhaps tell them about his business or his travels, but clearly this postcard serves its purpose.

“Gentlemen:

Where are the 2 M yds Braided Linen White

ordered. I must have at once or it will be too late.

Yours truly,

Thos. J. Conroy.”

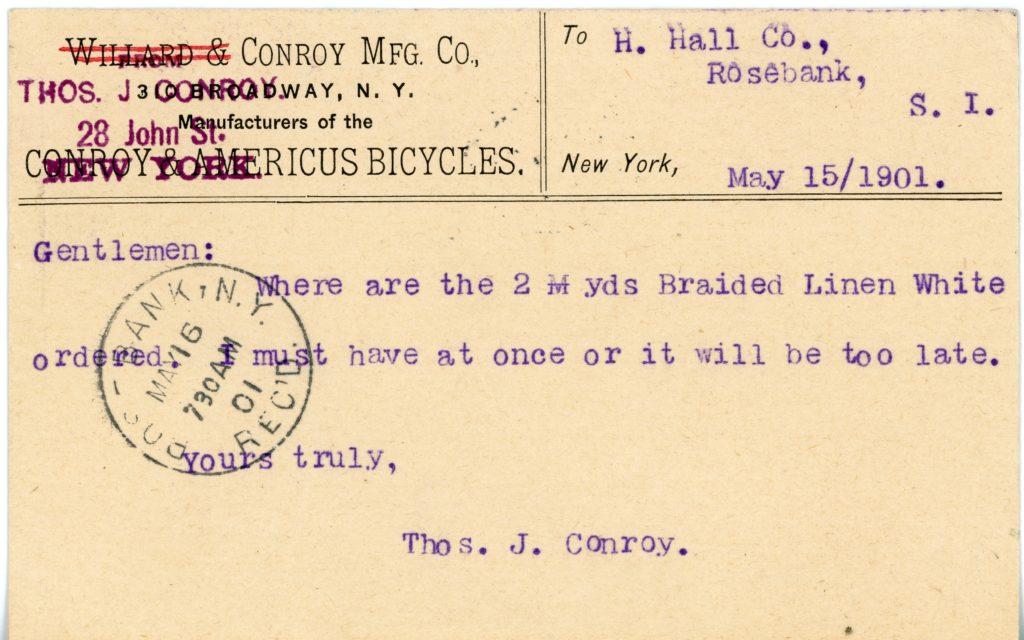

[Willard and Conroy Mfg. Co. Postcard] 1901. Gift of Peter Neill, 1997.034.0006

While this postcard may seem unique as it doesn’t have any kind of image on the card, it’s message is universally recognizable.

This message from 1901 shows how similar people are, even after over 100 years. While the format has certainly changed (no one today would mail a postcard questioning the delivery status of something they’ve ordered), this is a message many of us have sent. Postcards are uniquely able to show us these small mundane moments in life, some of which never change.

“Dear Geo,

Mr & Mrs Hill

Harold, Dad & I are having

our supper on

this boat, what do you think of this

Momma”

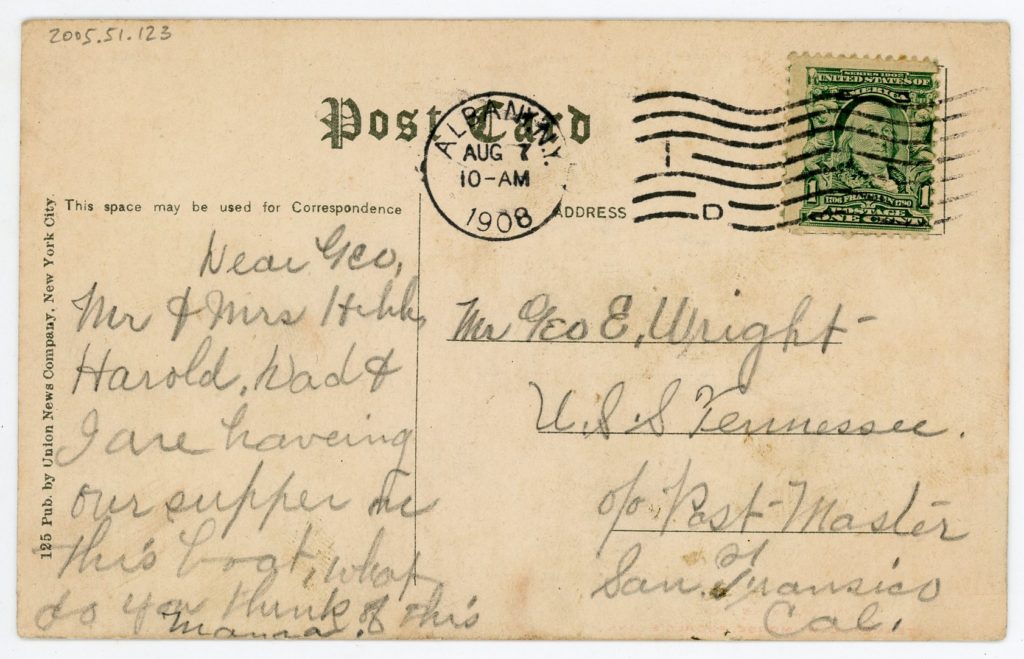

“Main Dining Hall, Steamer C. W. Morse, People’s Line” August 7, 1908 (postmark date). Gift of Wendell Lorang, 2005.051.0123

This postcard shows the main dining hall of the Steamship C. W. Morse, one of the luxury steamships of the Peoples’ Line which carried passengers between New York City and Albany daily from 1903 to 1927. Its message shows us another small moment from someone’s life, a mother wanting to share where she had supper and with whom. This is the kind of personal, everyday moment that gets immortalized in a postcard.

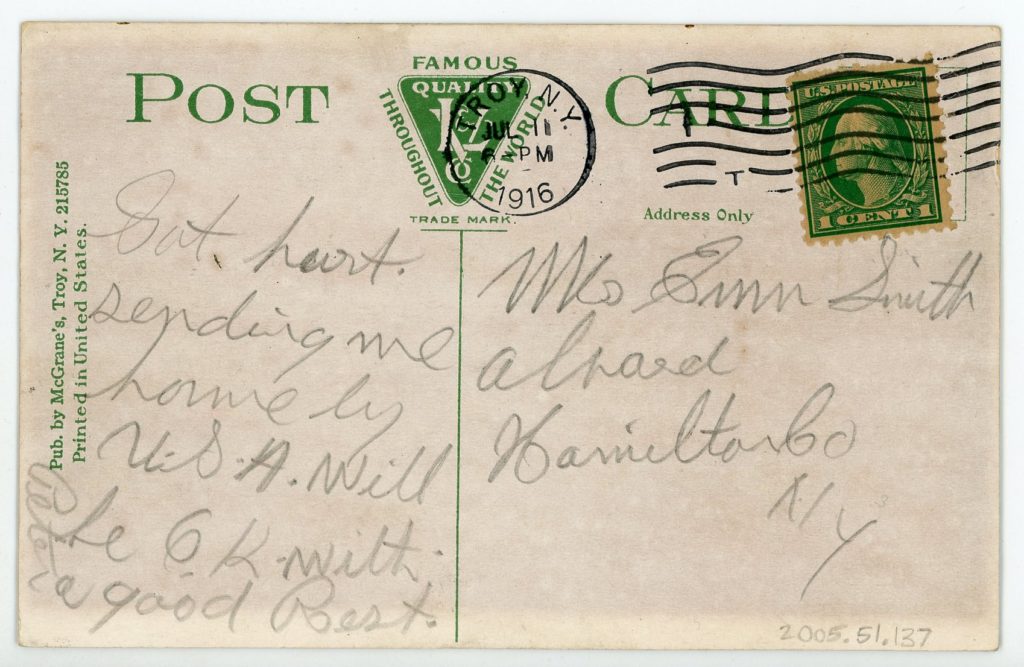

Occasionally, postcards can have a message that is not as casual as simple travels. One such message comes from a man named Peter, who wrote on the back of a postcard,

“Got hurt.

sending me home by

U.S.A. will

be OK with

a good Rest.

Peter”

“SS “Trojan,” Troy, N. Y.” July 11, 1916 (postmark date). Gift of Wendell Lorang, 2005.051.0137

This may initially seem like a strange, blunt message that would cause more questions than it would answer, but there is a lot of information to look at on a postcard beyond just the handwritten message. This postcard was postmarked on July 11, 1916, in the middle of World War I. This postcard is almost certainly being sent by a young soldier back home to his family in New York letting them know perhaps the best news they will ever receive, he’s coming home and he’ll be okay. In this instance, the postcard was probably what he had on hand to mail, and for only one cent he was able to tell his family the important things, and anything else could wait.

These are just a few of the voices of the past which we have in our collection. Postcards are a very broad category of ephemera and even in just these few examples there is quite a bit of variety in the stories which we can pull from each one. They perhaps include so many different kinds of stories because they were widely accessible, being the cheapest way to send a message in the early 20th century when many of our postcards were sent. Postcards become a way to look back at the lives of everyday people and their everyday lives, through their own words.

Postcards at the Seaport Museum

Postcards are very important at the Seaport Museum because they’re very important to New York City’s history, and its maritime heritage, which is a direct factor in the city’s global prominence today.

Many people came in and out of New York’s port, to travel, to work, and to immigrate. Postcards were an important tool of communication for all kinds of travel as they were a cheap way to tell friends and relatives that you were traveling and had arrived. Postcards can tell us when and why people were traveling and who and what they saw. The images that get printed onto postcards also tell us about important sites that were commemorated or perhaps popular to visit.

The Seaport Museum’s collection of postcards includes a variety of different postcards, many of which were sent in the early 20th century during the “Golden Age” of postcards.

The Seaport Museum’s postcard collection includes a variety of both maritime and New York City specific postcards. The ships and sights that appear on these postcards show the places which were noteworthy at the time, many of which are still recognized today as New York landmarks.

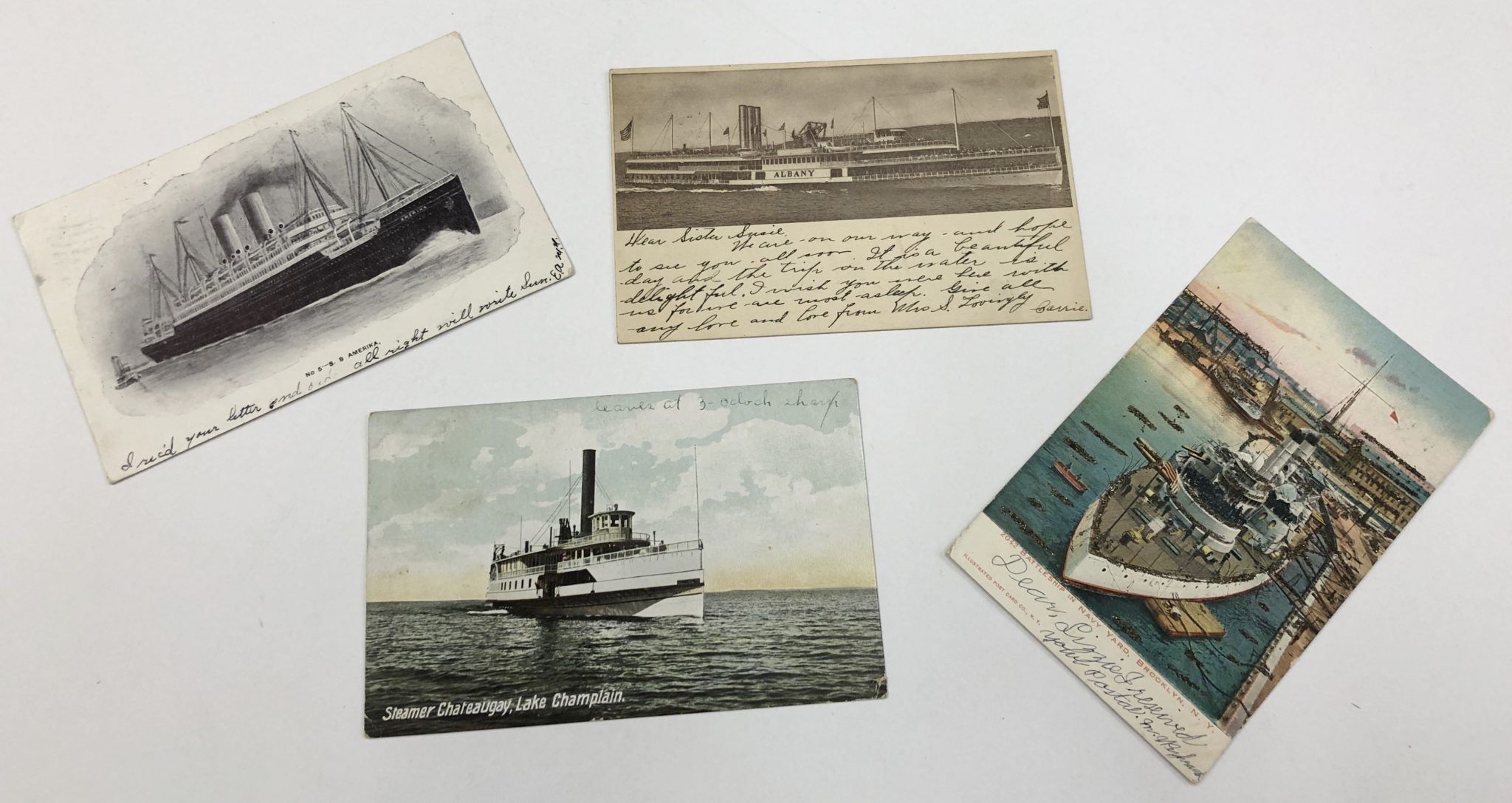

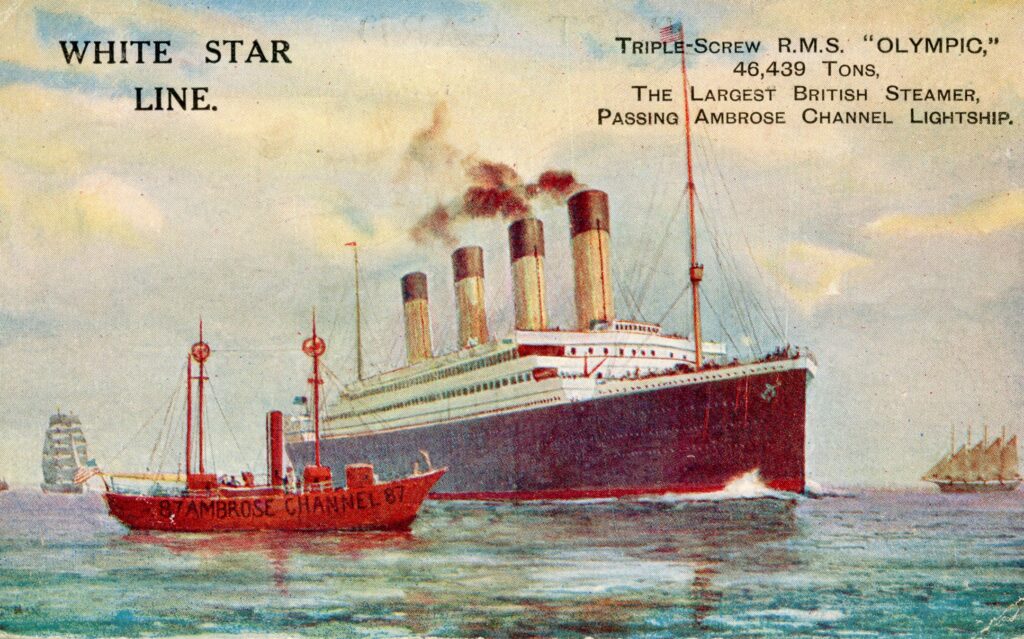

Many of the maritime postcards in the collection depict ships, some historic, but many are passenger liners which brought people to and from New York City. Before air travel was common and before New York’s current commuter rails were in service, these luxurious steamships were how people traveled upstate and they are prominently featured on many of our postcards. These cards in particular were likely souvenirs for passengers to be able to share and send out to friends and family to tell them about their travels and the amazing steamships they traveled on.

This recently acquired postcard depicts the British passenger liner RMS Olympic steaming past the Ambrose Channel Lightship as she approaches New York City. This postcard is one especially interesting to the Museum, as our very own Ambrose lightship is featured prominently on the postcard. She’s shown doing her job at the Ambrose Channel, while she now sits at Pier 16 and is cared for by the Museum. If you’ve been to Pier 16 she may look familiar in the postcard, but she wasn’t always painted red as she is now, and at the time of the printing of this postcard she wasn’t either! During her career stationed at the Ambrose Channel, between 1908 and 1932, she would have been straw color (light yellow) with black lettering painted on the sides until 1929, and from 1929-1932 she was painted black with white lettering.This postcard is dated ca. 1920s, and we think the artist or colorist painted her red as in the United Kingdom, where lightships at the time were red.

“Triple-Screw RMS Olympic, 46,439 tons, Passing Ambrose Channel Lightship” ca. 1920s. Gift of Michael Harrison, 2020.005

Here at the South Street Seaport Museum we have over 22,000 postcards catalogued, and even more that we have been working to document, digitize, and research. Our postcards are very important pieces of ephemera to tell the story of New York, its port, piers, and waterfront landscapes, as well as New York international trade routes, global cultures and seafaring, and including all aspects of life, art, and work associated with them.

While you may have a wonderful collection of postcards that also tell the history and stories of your family, New York, or another port, please do not send them to the Museum. With nearly 60,000 items in the collections, the Museum follows strict criteria when determining whether to accept new pieces. Factors include not only storage but long-term management costs and potential for research and exhibition use, and it is unlikely we will be able to accommodate your postcards due to our focus on cataloguing and researching the artifacts acquired in the past four decades, as well as our mission, and the space and resources we currently have available. To learn more visit the Museum’s Acquisition Guidelines on our website, or reach out to the Museum’s Collections and Curatorial staff at [email protected].

Conclusion

Over the course of my time with the South Street Seaport Museum as a Collections Intern I have been cataloguing a collection of postcards that depict various passenger steamships that mostly worked daily in and out of New York City in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. About half of the steamboats that I encountered worked on the Hudson River, but there were some that worked on other rivers, the Finger Lakes in New York, or the Great Lakes. These steamships seem to me to be the height of luxury travel of their day. Many of them had countless staterooms for passengers as well as fine dining rooms and the fanciest included countless other amenities, as well as of course the beautiful river or lake views from their decks.

Cataloguing these postcards, despite many depicting late 19th and early 20th century steamships which often shared the same journey of doing a lot of business until the rise of cars and air travel, and then being decommissioned or seized by the government for use in World War I, each new postcard brought me a mystery.

First was the ship and looking into where she worked and what line she served and any large events in her career such as disasters on the water, being sold to a new company on a new line, or being entirely refitted for a new role.

My favorite part of looking into the postcards however was the messages sent on them.

As you’ve seen from those I’ve profiled, many of the messages don’t necessarily paint a full image of a person or their situation, but that’s where the fun is. From what was written, and what I have researched about these steamships and New York at the time these postcards were sent, I was able to put together plenty of probable stories surrounding these people and the ephemera they left behind. –Emily D.

Over the course of my internship at the Seaport Museum, I feel like my understanding of what a museum even is has been expanded. Cataloging these postcards was not an easy task. It challenged me to keep myself precise and focused, while also playing around with what makes me curious. Oddly enough, I really enjoyed researching the difference between postal cards and postcards, or when and where the first couple postcards were printed. I wanted to answer as many of my questions as I could, and be as precise as possible. Postcards are a perfect medium for solving mysteries like these! I felt a little like Sherlock Holmes taking a magnifying glass to a photo so I would get a better look at a sign that was too small to read online. It feels really great to be able to catalog the information I’ve learned so that the Museum and future interns could use it for their own projects.

I wasn’t just confined to the 2D world, however, I also had the chance to handle, photograph, and take dimensions of some really great 3D objects as well.

After looking at postcards for so long, I was struggling to get my tape measure to fit through the crevices of sextants and octants, which are a little harder to handle than a 3×5 piece of paper.

I had a lot of fun opening up these boxes (some of which were a couple hundred years old) and seeing what’s inside. I’m excited for all of our work to go up on the Collections Online Portal soon! –Julia L.

Last, but not least, we just want to mention we’re not the only interns at the South Street Seaport Museum this summer. Over at Bowne & Co. some of our fellow interns have designed and printed their own postcard to honor the small businesses we love and which are vital to the Seaport community. While we love postcard history, postcards are still printed and used to this day! Have a look at the Bowne & Co. Instagram account for more information on both modern and historic letterpress printing, and visit the bowne.co online shop and pick up a postcard to mail and become part of postcard history yourself.

Additional readings and resources

“Greetings from the Smithsonian A Postcard History“, Smithsonian Institution Archives.

“The Mystery of the Undated Postcards” by Leah Tams, Intern, Institutional History Division, Smithsonian Institution Archives, July 23, 2013.

“Using Postcards for Local History Research” by Carmen Nigro, Managing Research Librarian, Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History & Genealogy, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, December 4, 2015.

“Historical Postcards of New York City from the Picture Collection” by Jessica Cline, Picture Collection, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, November 29, 2017.

Support Our Work!

Virtual programs like this one are provided at no cost in order to serve our community in unique and engaging ways, no matter where you might be in the world. Help us make this work possible.